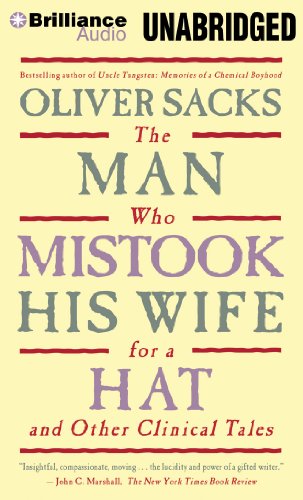

In his most extraordinary book, “one of the great clinical writers of the twentieth century” (The New York Times) recounts the case histories of patients lost in the bizarre, apparently inescapable world of neurological disorders. Oliver Sacks’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat tells the stories of individuals afflicted with fantastic perceptual and intellectual aberrations: patients who have lost their memories and with them the greater part of their pasts; patients no longer able to recognize people and common objects; patients stricken with violent tics and grimaces or who shout involuntary obscenities; patients whose limbs have become alien; patients who have been dismissed as retarded yet are gifted with uncanny artistic or mathematical talents. If inconceivably strange, these brilliant tales remain, in Dr. Sacks’s splendid and sympathetic telling, deeply human. They are studies of life struggling against incredible adversity, and they enable us to enter the world of the neurologically impaired to imagine with our hearts what it must be to live and feel as they do. A great healer, Sacks never loses sight of medicine’s ultimate responsibility: “the suffering, afflicted, fighting human subject.”

Fascinating The first thing I did after reading this book was to hop back onto Amazon.con and order “Awakenings” and “An Anthropolgist on Mars.” This book was recommended by one of my philosophy professors in college about six years ago. Well, it took me six years to pick it up, and I don’t regret the decision. As a complete layperson, my eyes were opened to what a complex piece of machinery the brain is. Sack’s personal perspective on these patients disorders is what takes…

Truly incredible tales and a great read It is utterly fascinating to know that, as a result of a neurological condition, a man can actually mistake his wife for a hat and not realize it. It is also fascinating to learn that a stroke can leave a person with the inability to see things on one side of the visual field–which is what happened to “Mrs. S.” as recalled in the chapter, “Eyes Right!”–and yet not realize that anything is missing. In both cases there was nothing wrong with the patient’s eyes; it was the…