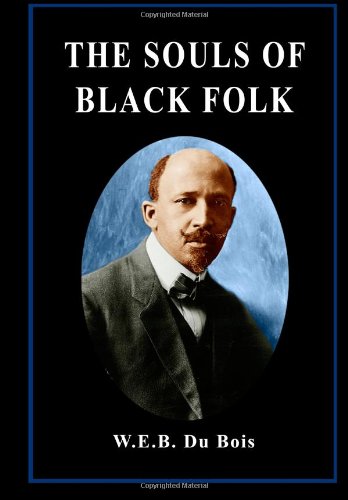

The Souls of Black Folk is a classic work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology, and a cornerstone of African-American literary history. The book, published in 1903, contains several essays on race, some of which had been previously published in Atlantic Monthly magazine. Du Bois drew from his own experiences to develop this groundbreaking work on being African-American in American society. Outside of its notable place in African-American history, The Souls of Black Folk also holds an important place in social science as one of the early works to deal with sociology. Chapter I lays out an overview of Du Bois’s thesis for the book: that the blacks of South need the right to vote, a good education, and to be treated with equality and justice. The first chapter also introduces Du Bois’ famous metaphor of the veil. According to Du Bois, this veil is worn by all African-Americans because their view of the world and its potential economic, political, and social opportunities is so vastly different from that of white people. The veil is a visual manifestation of the color line, a problem Du Bois worked his whole life to remedy. Du Bois sublimates the function of the veil when he refers to it as a gift of second sight for African-Americans, thus simultaneously characterizing the veil as both a blessing and a curse.[1] The second chapter, “The Dawn of Freedom” covers the history of the Freedman’s Bureau during reconstruction. Chapters III through VI focus on education. Du Bois argues against Booker T. Washington’s idea of focusing solely on industrial education for black men, and advocates the addition of a classical education to establish leaders and educators in the black community. Chapters VII through X are sociological studies of the black community. Du Bois investigates the influence that segregation and discrimination have had on the black people. He argues that much of the negative stereotypes of blacks as lazy, violent, and simple-minded are results of the treatment from white people. In “Chapter X: Of the Faith of the Fathers”, Du Bois describes the rise of the Black church, and examines the history and contemporary state of religion and spiritualism among African-Americans. The final chapters of the book are devoted to narratives of individuals. “Chapter XI: Of the Passing of the First-Born” tells the story of Du Bois’s own son and his untimely death. In the next chapter, the life of Alexander Crummell is a short biography of a black priest in the Episcopal Church. “Chapter XIII: Of the Coming of John” is the fictional account of a boy from Georgia who goes off to college and, on his return is rejected by both his black community and the white patricians of his town. The last chapter is about Negro music and makes reference to the short musical passages at the beginning of each of the other chapters. In Living Black History, Du Bois biographer Manning Marable observes: Few books make history and fewer still become foundational texts for the movements and struggles of an entire people. The Souls of Black Folk occupies this rare position. It helped to create the intellectual argument for the black freedom struggle in the twentieth century. Souls justified the pursuit of higher education for Negroes and thus contributed to the rise of the black middle class. By describing a global color-line, Du Bois anticipated pan-Africanism and colonial revolutions in the Third World. Moreover, this stunning critique of how ‘race’ is lived through the normal aspects of daily life is central to what would become known as ‘whiteness studies’ a century later.William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) is the greatest of African American intellectuals–a sociologist, historian, novelist, and activist whose astounding career spanned the nation’s history from Reconstruction to the civil rights movement. Born in Massachusetts and educated at Fisk, Harvard, and the University of Berlin, Du Bois penned his epochal masterpiece, The Souls of Black Folk, in 1903. It remains his most studied and popular work; its insights into Negro life at the turn of the 20th century still ring true.

With a dash of the Victorian and Enlightenment influences that peppered his impassioned yet formal prose, the book’s largely autobiographical chapters take the reader through the momentous and moody maze of Afro-American life after the Emancipation Proclamation: from poverty, the neoslavery of the sharecropper, illiteracy, miseducation, and lynching, to the heights of humanity reached by the spiritual “sorrow songs” that birthed gospel and the blues. The most memorable passages are contained in “On Booker T. Washington and Others,” where Du Bois criticizes his famous contemporary’s rejection of higher education and accommodationist stance toward white racism: “Mr. Washington’s programme practically accepts the alleged inferiority of the Negro races,” he writes, further complaining that Washington’s thinking “withdraws many of the high demands of Negroes as men and American citizens.” The capstone of The Souls of Black Folk, though, is Du Bois’ haunting, eloquent description of the concept of the black psyche’s “double consciousness,” which he described as “a peculiar sensation…. One ever feels this twoness–an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Thanks to W.E.B. Du Bois’ commitment and foresight–and the intellectual excellence expressed in this timeless literary gem–black Americans can today look in the mirror and rejoice in their beautiful black, brown, and beige reflections. –Eugene Holley Jr.